This piece was originally published in Growing America on January 29, 2016.

I first became aware of a divided opinion about American farming after reading Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma in 2007. I had been working on the family farm in North Georgia—cleaning out chicken houses, selling Christmas trees, watching the cows chew their cud, and not knowing there was anything different. The grinding noise of progress was everywhere, as residential and commercial development obliterated the pastures and woods. I was an overly educated young man, watching the pastoral environment I had grown up in eliminated, on a farm without enough income or responsibilities for everyone in the family.

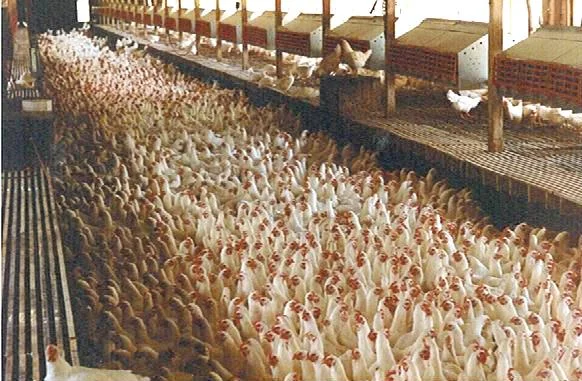

Pollan opened up a new way of seeing my own little word. Suddenly it was obvious that commodity production had logical inconsistencies and questionable outputs that seemed to threaten local communities and physical health. I could see firsthand that our farm and the farms around us could barely sustain themselves, much less a vibrant local economy. The absurdity that we drove our bulls 45-minutes to the auction and then picked up frozen hamburger at Publix on the way back had never occurred to me. We had 35,000 chickens, 250 head of cattle, and 500 acres of beautiful hills and bottoms, yet the only food the farm produced for us were some double-yolk eggs and a few pecans that hit the ground each year.

The Omnivore’s Dilemma seemed to offer a hopeful vision of profitability, entrepreneurship, environmental sustainability, and wellbeing. At the time I couldn’t identify the nearest farmers market, and I had never met anyone who had shopped at one. Selling locally with premiums based on production practices was an entirely novel concept. While it justly contained some inherent critique of the system that my family’s farm operated within, the idea of small, organic and local was misconstrued by myself and many others as the alternative or “right” way to farm when, practically-speaking, we should have seen it as another or additional way to farm.

From that point, I think those involved in food culture made the grievous mistake of differentiating between groups of good farmers and bad farmers. Good farmers were small, young, sexy, educated, technologically-savvy; they cared about their communities because they sold and shopped locally; they conserved the earth’s natural resources; and they grew myriad nutritious things you could eat raw. Bad farmers were big, older, fat, dull, largely invisible behind their giant machines. Under a deluge of synthetic chemicals, they grew endless rows of exhausting monocrops to export globally, create animal fat, and process into oils, sugars and random carcinogens. Facing those options, the preference for most American consumers was obvious, the idealistic underdog over the pawn of Big Ag. The internet only reinforced those decisions with infinite access to information, misinformation, and confirmations of personal prejudice. Food marketing and issue organizations used both the farmers and consumers for their own purposes.

But the reality has always been something entirely different, and it goes straight to the almost impossible risk intrinsic to farming. Arising from the privations of the Great Depression and the resource demands of World War II, the American agricultural system has evolved, through integration and scale, with a single-minded imperative to maximize efficiency and productivity. It has also minimized the crushing risk that has beset farmers from the beginning of time: variability in weather, poor markets, insufficient pricing data, capital limitations, labor, distribution, and physical exhaustion—to name a few. A crop like soybeans requires little to no manual labor, can be hedged to protect profits, and will take storage until the market is ready. The Federal government, which according to its own terms is compelled to ensure “an adequate and reasonably priced supply of food and fiber,” will subsidize its production because a soybean is less perishable and more densely nutritious than an equal weight of tomatoes, for example.

Those bad farmers with their miles of inedible row crops all made logical decisions about diversity, inputs, machinery, and government programs that enabled them to keep their farms, provide for their families, take vacations, and go to town and to church with their heads high. Their farming practices allowed them to live the typical American lifestyle. By producing food inexpensively, they also allowed everyone to live the typical American lifestyle. The very fact that, in 2013, Americans spent only ten percent of their income on food meant they had the money to enjoy the luxury of free time. As far as environmental concerns, the bad farmers never practiced anything they believed would injure their families or the land that produced their wealth.

Meanwhile, the good farmers learned the old lessons about farming’s risk. I have felt personally and watched again and again the struggle to grow fruits and vegetables for a local market. The physical and mental strain to manage mixed specialty crop operation can be overwhelming. For an organic production system, the market rarely offers a price that covers the true cost of your time and labor, especially on a small scale. While shoppers rhapsodize over your carrots and chefs rush to put your farm’s name on their menus, you’re pushing off student loan repayment, praying you can avoid hospital bills, and trying to find a sliver of profit on your spreadsheet.

Which is all to say, maybe we need to reassess the current state of agriculture and Pollan’s impact a little bit. The folks on the “good” side jumped the gun into thinking The Omnivore’s Dilemma was a manifesto, and they could overturn 70 years of rational, science-based thought overnight. More realistically, in his book Pollan was highlighting an emerging value proposition for local and sustainable sales, more robust initially in places like the Northeast and the West Coast. Instead of wholesale revolution, advocates of a different kind of agriculture should have (and should still) think about pragmatics over ideals, increasing market share over transformation.

For the “bad” side, Pollan offered a healthy examination of the conventional agricultural system and its ability to meet both the demands of the global commodity marketplace and the changing appetites of American consumers in the twenty-first century. The agribusiness and farming complex seemed to be quicker to circle the wagons than consider new opportunities. In reality, Pollan was simply pointing out consumer trends for humanely-raised meat, foods without additives and preservatives, fair labor standards, and less caustic chemical inputs that are playing out today.

Unfortunately, what emerged from all that was a debate and not a dialogue. A conversation that should have been had about good food became a question about the morality of farmers. But in my experience those are distinctions that are not held by the farmers themselves. Farmers are farmers. Good, bad, big, small, they respect and help each other more than anyone outside their number ever has.

The truth is that it’s time to move beyond sides. We face incredible challenges in the next century to feed the world, protect water, preserve biodiversity, reverse desertification, and capture carbon from the atmosphere. We need healthier diets, more balanced lives, stronger rural economies, and greater peace. As with any collaboration, there will be conflicts about method, but we start on the same page. We will take the best ideas and we will do it together.