The Farm Bureau article on national bankruptcy trends for agricultural producers has been making the rounds, and the number for Georgia — at 37 tied for second most behind Wisconsin — stick out. Wisconsin’s ranking likely owes to the troubles that have shaken the dairy industry of late. (In fact, Dean Foods, the nations’ number one milk producer, just filed for bankruptcy.) The situation in Georgia is a striking contrast against neighboring states, and perhaps it shows the impact of the “trade war” on cotton producers and even the lasting damage of Hurricane Michael.

But there are some things to consider:

Per the AJC, the number of farmers who filed for Chapter 12 through September 30 is up 12 from the same period in 2018. However, that amount was 43 and 41 in the two previous years.

Georgia is doing fine in Market Facilitation Program (MFP) payments, that series of magical remunerations for farmers’ sacrifice during the “trade war” with China. To date, Georgia has received $151,605,594.10. By comparison, Alabama has only gotten $55,610,083.70

On November 15, Secretary Perdue announced a second tranche of MFP payments to be paid starting the week of Thanksgiving. For producers of MFP-eligible commodities, this now covers 75% of the potential total payment from MFP. For reference, MFP will provide as much as $14.5 billion in direct payments to farmers.

The USDA will consider issuing a third round of MFP payments based on market conditions. You can take it to the land bank that this will happen. That Farm Bureau article estimates that 40% of farmers’ income (i.e. $33 billion) “is related to trade assistance, disaster assistance, the farm bill and insurance indemnities.” In a year of bad weather, these payments are helping keep farms afloat. The only question is when. Farmers will need them ASAP to fund and finance 2020 crops. But political cycle may hold them up until it’s most advantageous for Trump’s reelection campaign.

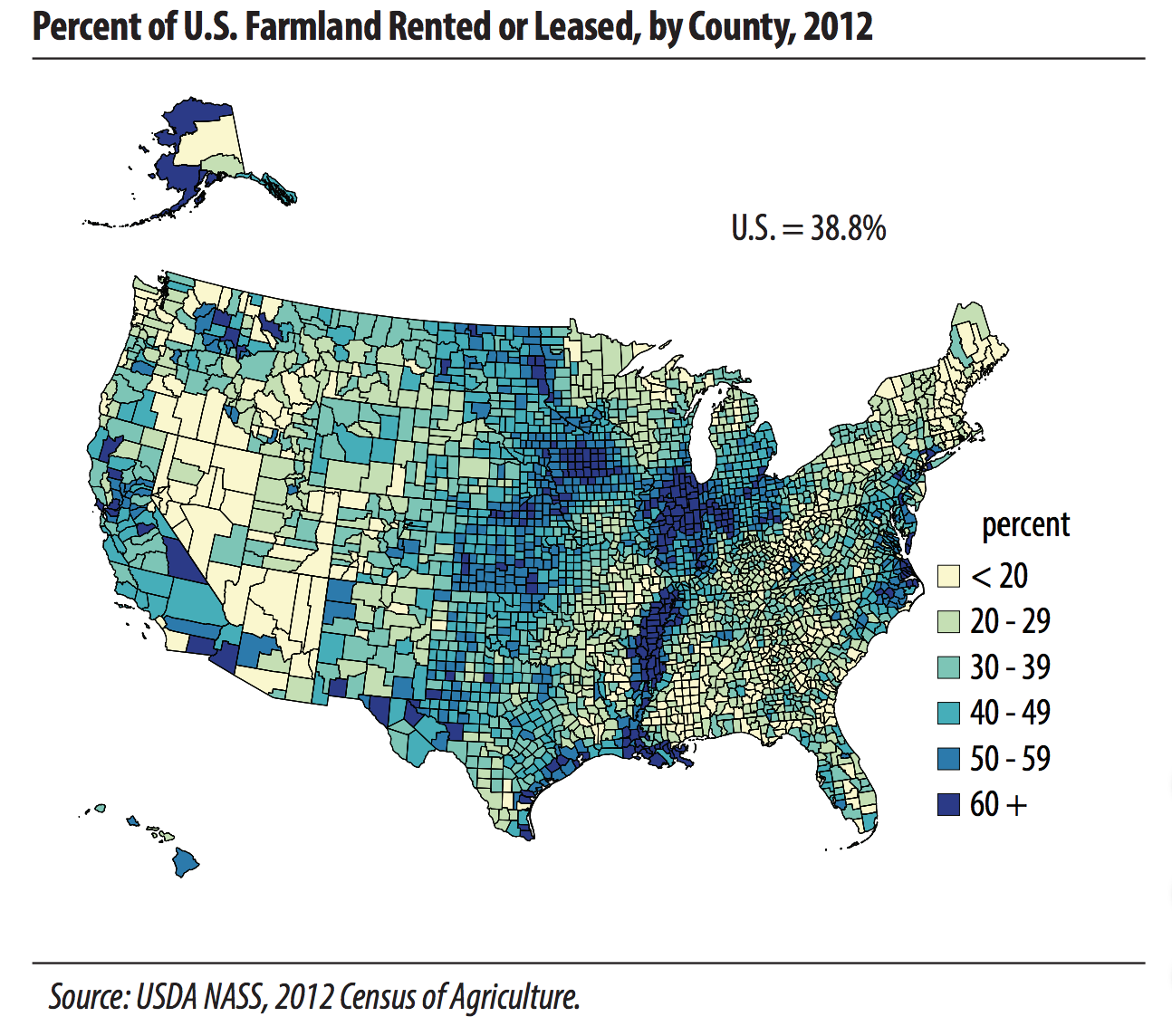

In the midst of the storm and stress around farm bankruptcies and hard times in the heartland, it’s worth considering concentration in the industry and the growth of mega farms, for good or ill.

Five percent of all farms produce 75% of all sales, and the trend line is falling. These figures come from Brent Gloy of Agricultural Economic Insights using data from the USDA NASS Census of Agriculture.

Interestingly, Gloy points out that these large farms are also responsible for a disproportionate amount of Certified Organic production. Out of a total of $7.27 billion, 43 had organic sales of $1.3 billion and 945 had sales of $4.6 billion. In other words, less than a thousand farms account for over 60% of all organic sales.